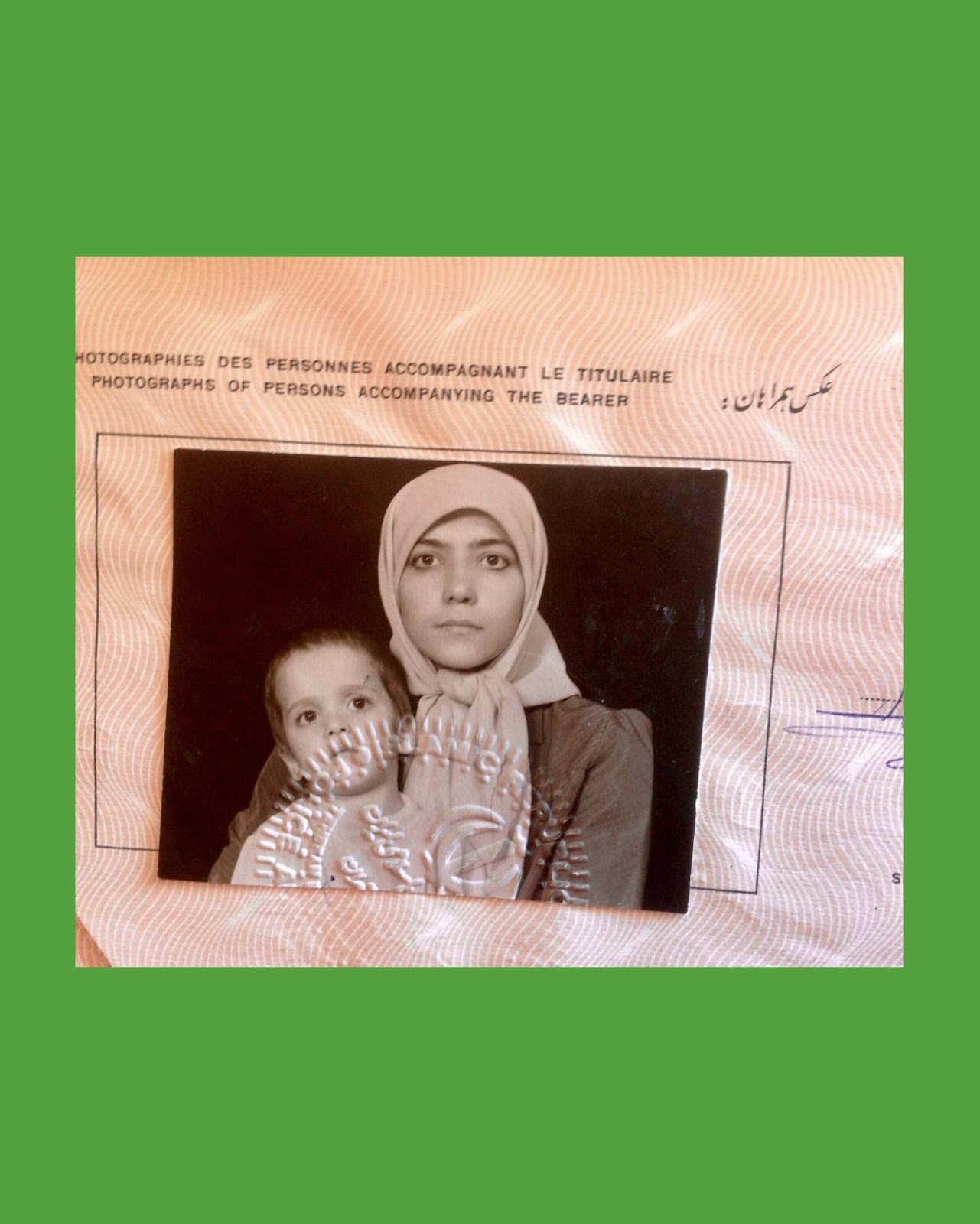

My grandparents, Ely and Raymonde Bouaziz, were born in Tlemcen, Algeria. In the 1940s, when tensions between the Algerian independence movement and the French authorities were rising— eventually culminating in the Algerian war—they emigrated to Kenitra. A short time after, as similar tensions broke out in Morocco, a deranged man attacked my father on the head with a baton while he was at school. This violent episode prompted them to move again, this time to France.

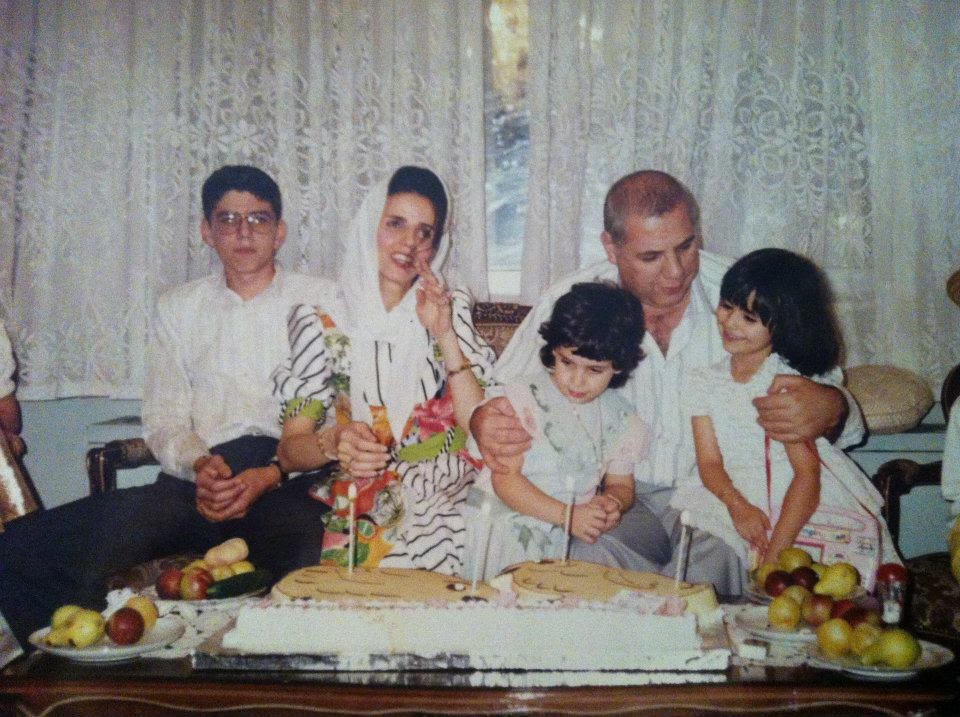

In the early 1950s, when my father was six years old, my grandparents and their four children arrived in Paris. They were poor and for a while lived among other migrants and outcasts in a shoddy hotel on the outskirts of the city. I don’t know much about my grandmother because she was always discrete and silent. I remember only her hugs. I can’t say exactly what my grandfather did for a living when they arrived in France, though I know he had many lives before and after migrating.

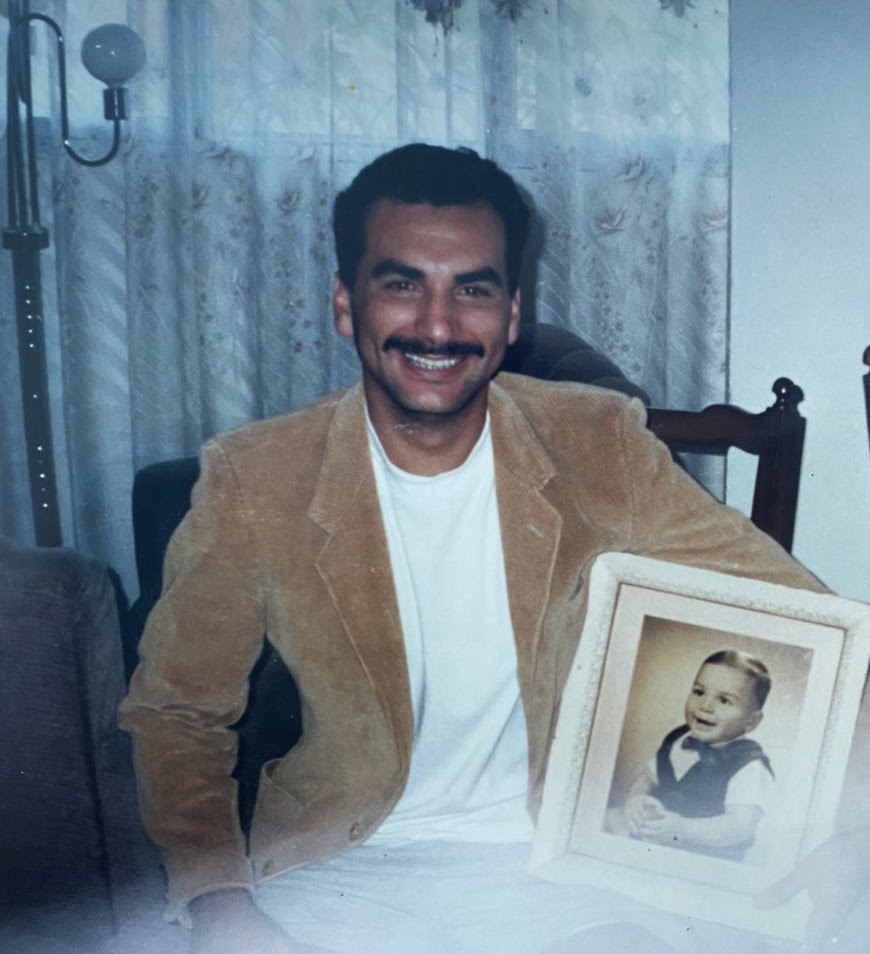

In his youth in Algeria, he was destined to become a Rabbi but quickly rejected religious hierarchy and in the process became a brilliant Cabbalist. Later, he became a photographer at a time when taking pictures was still considered a form of sorcery. In Morocco, he ran a cinema that screened Westerns, films that my father still loves to this day.

He was also a magician and narrated extraordinary stories of the paranormal. Later in his life, he became a pharmacologist with a license to buy raw medical products from laboratories and treated whoever got sick in his family. In the mid 1980’s he went on to research a cure for AIDS. He patented a food supplement for cattle. He wrote two books, one about psychoanalysis in relation to physical behavior and posture, and another about hand and palm reading. In his free time he was a painter, and it is even rumored he was a spy who helped Algerian activists seek refuge in Morocco back in the 1940s. True to his compulsion to connect and heal, he also played the oudi a facet of his life I only recently discovered.

Unfortunately, my grandfather was not attached to memorabilia—perhaps because of his acute memory—so he never wrote down or recorded his stories. Though at its core, isn’t that what immigration is about: stories that travel, stories that get lost and finally forgotten. Stories that are translated, adapted. Stories that are passed on and that eventually become myths.

Press play below to hear a recorded track by Ely Bouaziz digitized and edited by his grandson Joakim.